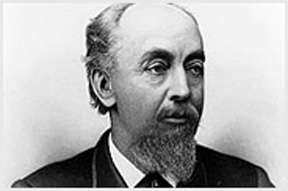

William LeBaron Jenney designed the world’s first steel-frame skyscraper in 1885, creating a new style of construction which would come to define the city. You can still see some of his groundbreaking architectural masterpieces in downtown Chicago using this free self-guided William LeBaron Jenney walking tour.

As the inventor of the skyscraper, Jenney trained talented young minds who also made their mark on Chicago. He mentored famous architects like Daniel Burnham, Louis Sullivan, William Holabird, and Martin Roche. William LeBaron Jenney’s innovations and influences are vast, yet his work is somewhat overlooked these days. Even yours truly, a proud Chicago history and architecture geek, didn’t realize just how many Jenney buildings are still standing in Chicago. So I created a list of William LeBaron Jenney’s contributions to Chicago architecture that you can tour on your own. This quick walk is designed to give you a glimpse of Jenney’s genius and his lasting influence.

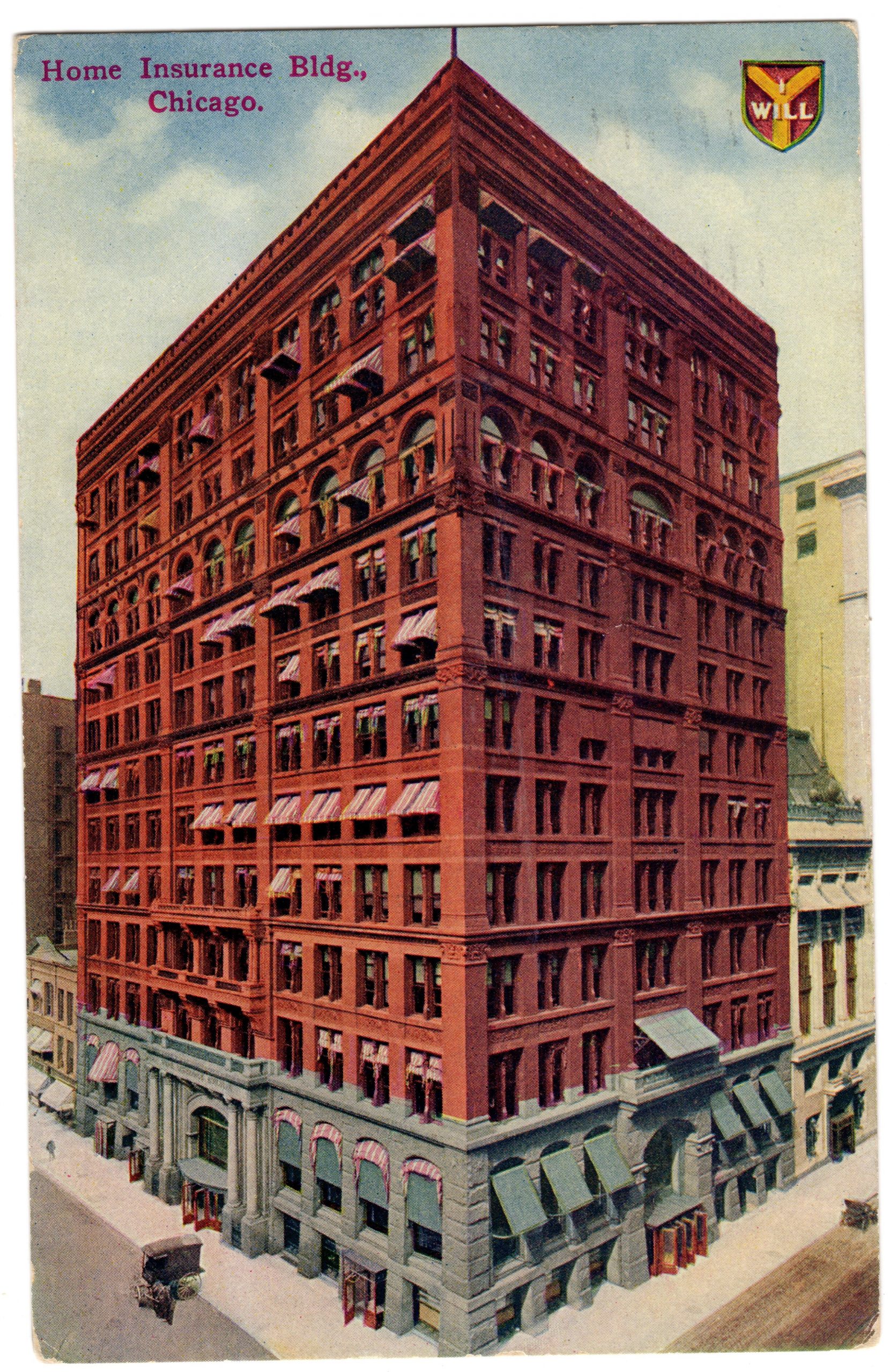

The Home Insurance Building

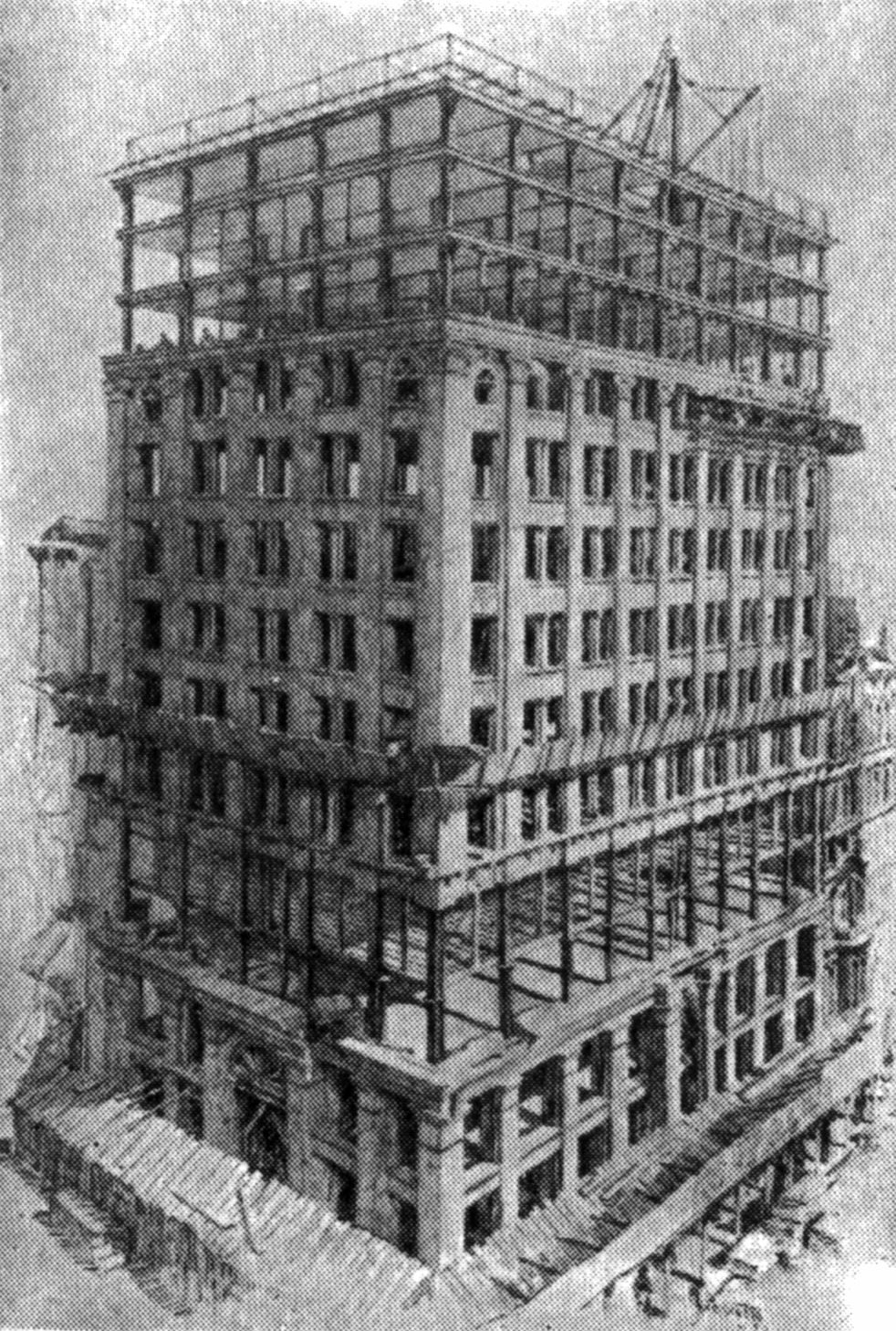

Our walking tour of William LeBaron Jenney’s work must begin, sadly, at the site of a landmark which is no longer standing. The Home Insurance Building, built in 1885 at Adams and LaSalle, was the world’s first skyscraper. Instead of relying on massive exterior walls, Jenney designed a spindly frame of fireproof steel and iron beams which bore much of this office tower’s weight. This engineering breakthrough allowed the building to rise higher, created more interior space and light, while weighing 1/3rd as much as a traditional tower and even adding extra fireproofing. It was truly a quantum leap breakthrough in architectural history.

Supposedly, Jenney’s inspiration came from seeing his wife set a book on a birdcage. The thin metallic bars could support the dense bookbinding, which inspired the idea that a skeleton frame of steel beams could support an office tower. Not everyone trusted Jenney’s work, though. The city actually shut down construction out of concern that the tower would inevitably collapse.

Th Home Insurance Building stood the test, of course, and everything from The Rookery to the Burj Khalifa is descended from the experimental design of William LeBaron Jenney. All of that said, sadly, the Home Insurance Building is no longer standing. A demolition crew knocked down the world’s first skyscraper in 1931. The site was cleared and the Field Building, a block-length Art Deco tower, was constructed in its place. Its beautiful lobby is worth a visit on its own, and you can pay a pilgrimage to a plaque in the lobby that marks the location of Jenney’s world-changing innovation.

The New York Life Insurance Building

Our William LeBaron Jenney walking tour continues a block north up LaSalle. Today’s Kimpton Gray Hotel occupies the New York Life Insurance Building, which William LeBaron Jenney designed back in 1894. Constructed less than a decade after the Home Insurance Building, it originally rose 12 stories above the LaSalle Street canyon, with two more stories added later. As its original name implies, the tower housed offices for Gotham-based insurance company. Like the Home Insurance Building a block away, Jenney’s tower helped consolidate LaSalle Street’s reputation as the heart of Chicago’s financial district. Jenney’s architecture conveyed wealth and power for the insurance company, which is why so many Downtown Bucket List private tours visit here.

The tower is one of the best extant examples of the Chicago School of architecture. Delicate Classical ornamentation in terra cotta adorns the facade, which is broken up into a tripartite design. Monumental gray limestone covers the base, lending the gravitas one expects from a financial institution. The bold vertical piers and horizontal bands express the steel frame which supports the structure. Unlike the Home Insurance, the New York Life Insurance Building narrowly avoided demolition. Indeed, the Kimpton poured millions into a restoration effort when they opened the Gray a few years back. It is as close as we can come to seeing Jenney’s original marvel.

The Manhattan Building

Heading down Dearborn from Monroe on this William LeBaron Jenney walking tour is a walk through skyscraper history which takes you to a pair of Jenney landmarks right on the southern rim of the Loop. The most immediately eye-catching is the magnificent Manhattan Building. Completed in 1891, this skyscraper was on the cutting edge of that era’s architectural and aesthetic revolution.

The building’s 16 floors are entirely supported by a skeleton frame of iron beams. At the time, the Manhattan soared several floors above any of its neighbors. Only Adler and Sullivan’s then-new Auditorium Building (which we visit on the 1893 World’s Fair Tour) leapt to such great heights.

Worth noting how breathtaking and anxiety-inducing a height like 16 stories felt like to people in the Gilded Age. Most homes back then were only 1 or 2 stories high and big commercial buildings of the Loop, like the Washington Block, were only 4 stories. For an architect like Jenney to triple a building’s height and do so with mere metal beams felt like the height of folly. One imagines that the Manhattan Building recalled the Tower of Babel for many a visitor to Chicago.

Jenney’s design incorporated multiple decorative materials (brick, granite, terra cotta) and ornate elements (projecting bays, classical decor, hidden faces) to break up the vertical facade. Even more importantly, Jenney’s exterior decor is arranged in horizontal, rather than vertical bands. This aesthetic choice distracted 19-century Chicagoans from the building’s gravity-defying height. That said, even these days the Manhattan dominates its corner, looming like a colossus above Printer’s Row.

Second Leiter Building

Our William LeBaron Jenney walking tour continues just two blocks east of the Manhattan with another of Jenney’s bold experiments in architectural form. The Leiter II Building, now the home of Robert Morris University, is an enormous steel-frame structure from 1891. Levi Leiter, Marshall Field’s original retail partner, commissioned the enormous building after a previous successful collaboration on the First Leiter Building.

Having a second shot at the unique challenges of a State Street department store, Leiter did not hesitate to pursue his vision. A cage of steel beams, rising eight floors, runs the entire 402-foot-long block. The exterior ornamentation is remarkably minimalistic for its time. Small capitals adorn the top of the piers, which separate its nine window bays, and colonnettes, which separate the window frames. Beyond that, a minimalistic cornice is the only other decoration breaking up the exterior’s pink granite cladding. The resulting structure is a boldly austere statement and a stark contrast with other department stores of that era.

Ludington Building

The last stop on our Jenney walking tour is a building I only learned of while researching this post. His Ludington Building, on Columbia College’s campus along Wabash in the South Loop, is a jaw-dropping masterpiece. The Ludington, built in 1889, is a two-fer of local architectural firsts. It’s both the oldest purely steel frame building and the earliest to be clad solely in terra cotta. The loft-style structure appears to float, angelic, in this formerly industrial neighborhood.

Jenney constructed the Ludington for the American Book Company, one of the old Printer’s Row mainstays. The loft-style construction suited their needs, namely printing presses and shipping spaces. That openness attracted later industrial tenants, like the auto supply company which used the Ludington as a warehouse until the 1990s. Columbia bought the newly-landmarked building in ’99, converting it into a chic post-industrial loft style that remains all the rage.

One can clearly see Jenney’s evolving aesthetics just by taking a glance at the Ludington. Perhaps because it didn’t soar as high, only 8 stories, the decor seems less tied to traditional elements. The creamy terra cotta uses classical forms, like candelabras, vines, and dentils. Yet those details are not emphasized on a Jenney walking tour. Instead, one’s eyes focuses upon the delicate interplay between wide-open windows and the bold framing of steel piers. I find it impossible not to see future landmarks like the Sullivan Center and Mies’ Federal Center lurking in Jenney’s experimental style.

A William LeBaron Jenney Walking Tour Through the Past

In writing this, I have found a deeper appreciation for Jenney’s role in Chicago’s architectural history. I’d long known his name and the significance of the Home Insurance Building, but it seemed like a one-off. I thought he’d overseen a world-changing breakthrough purely by chance and then shuffled away. Later names and thoughtless demolitions obscure his work. I couldn’t have been more wrong. Jenney’s aesthetics are perhaps not as fully developed or flashy as his successors, but they also had an advantage. Burnham, Sullivan and the rest stood on the shoulders of a giant named William LeBaron Jenney.

– Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide