Women’s History Month is a natural time to reflect on all the women who’ve made Chicago a world-class city. We’ve got some heavy hitters, of course. Nobel Prize-winner Jane Addams, Pulitzer Prize-winner Gwendolyn Brooks, and the force of nature that is Oprah. On Friday, March 22, we’re hosting our second annual “Badass Women of Chicago History,” a live storytelling event that will shine a light on some of the other awesome women from Chicago’s past, women whose names you may not know. Talented storytellers will share the challenges, triumphs and inspirational stories of a huge range of Chicago women from history.

Badass women are everywhere in Chicago’s history, of course, so to kick off Chicago Women’s History Month we’re spotlighting a few more you may not know.

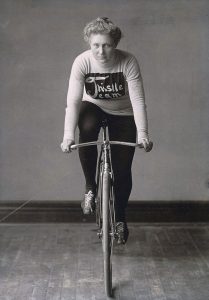

1. TILLIE ANDERSON, CHAMPION OF THE WORLD

Tillie Anderson was a badass woman who smashed cycling records during the height of Chicago’s late-nineteenth century bicycle craze. A Swedish immigrant, Tillie arrived in the city in 1889 and saved her meager seamstress’ earnings for two years to buy her first bicycle. She relished the freedom it gave her, and above all else she liked to go fast. In 1895 she entered her first bicycle race. By 1896, she was the undisputed champion of women’s cycling in the world.

Tillie was known to be, ahem, “strong-willed” and devoted to athleticism at a time when women were expected to be dainty and prim. She proudly showed off her muscles to a reporter in 1897, noting, “Three years ago I was very fat in the legs, almost as much so as Miss Peterson, one of my competitors in the St. Louis race, is today.” Oh the shade of it all.

She memorably completed a 100-mile course from Chicago through Elgin and Aurora and back. Incredibly, she completed the route in just under 7 hours. The Tribune noted in 1965 that “no girl ever broke Tillie’s record… and very probably no girl ever will.” Our resident cycling master (and Lead Tour Guide) Elizabeth confirmed for me that this trip would probably take her about 8 hours. Considering the advancements in bicycle technology that have been made in the last 120 years, I think it’s safe to say Tillie deserves a nod during Chicago Women’s History Month.

2. HAZEL M. JOHNSON, ENVIRONMENTAL WARRIOR

Hazel M. Johnson is often called “the mother of the environmental justice movement.” As a resident of the Altgeld Gardens housing project on the South Side, she noticed the extremely high rates of cancer, respiratory issues, and other health concerns in her own family and in the community around her. Her husband died of cancer in 1969 at the age of 41, which motivated her to act. She began investigating.

She discovered that Altgeld Gardens is built on a former landfill. Industry nearby polluted the land and air, and dangerous chemicals poisoned the drinking water. Digging further, she learned that a 140-square-mile ring of pollution stretched from the South Side of Chicago to northern Indiana, which she called “The Toxic Doughnut.” She galvanized her neighbors to form the organization People for Community Recovery to fight back.

Hazel was a badass woman of Chicago history who was unafraid to stand up for her community. “Every day, I complain, protest and object, but it takes such vigilance and activism to keep legislators on their toes and government accountable to the people on environmental issues,” she said in 1995. “I’ve been thrown in jail twice for getting in the way of big business, but I don’t regret anything I’ve ever done, and I don’t think I’ll ever stop as long as I’m breathing.”

Hazel revealed the environmental hazards which endanger many less-privileged communities. Her legacy is carried on today in the work of activists in Chicago neighborhoods who fight to ensure that their communities have access to healthy environments.

3. VALERIE TAYLOR, REVOLUTIONARY WRITER

Born Valerie Nacella Young in rural Illinois, this badass woman of Chicago history married in her 20s and soon had three sons. Unfortunately, her husband was unstable and abusive. She sold her first novel in 1953 for $500, and used that money to hire a divorce attorney. Valerie packed up her sons and moved into a tin-walled house in Chicago.

She soon found success writing lesbian pulp novels, which were exploding in popularity in the 1950s. However, men wrote most of these books. Valerie wanted to add some realism to the genre. “I wanted to make some money, of course, but I also thought that we should have some stories about real people,” she later said. Under the pen name Valerie Taylor she published her first novel in this genre, The Girls in 3-B. It sold 2 million copies, a smash success.

She told her biographer that she was an “inevitable revolutionary” because society deemed her an “eight-time loser: I am a woman, a lesbian, a creative spirit, a laborer, a handicapped person, a peace worker, an Indian (Potawatomi), and over sixty.” She was a founding member of Mattachine Midwest in 1965 and devoted her life to numerous causes including tenants’ rights, peace activism, and in her later years was an active member of the Gray Panthers. For all those reasons, she deserves a place of honor during Chicago Women’s History Month.

4. CHIYE TOMIHIRO, FEARLESS WITNESS

When Chiye Tomihiro was 16 years old, she and her family were forced to leave their Portland, Oregon home and report to an “evacuation center” ringed by barbed wire fence. It was May 1942, one month before Chiye was going to graduate from high school. She was among the over 100,000 people of Japanese descent (mostly American citizens) who were relocated into internment camps during World War II.

Over 20,000 displaced Japanese Americans resettled in Chicago after the war, including Chiye and her family. She recalled facing discrimination in housing and struggling to find a job. Suspicion, and outright racism, against Japanese-Americans was omnipresent right after the war.

After the war Chiye and most of the relocated Japanese-American community focused on recovery. By the 1960s, she began to vocally advocate for civil rights and official recognition of the injustices endured during the war. She testified before Congress at the 1981 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment on Civilians. She spoke boldly about her own experiences and arranged for others to testify, which many were reluctant to do.

“I think for the first time they faced up to what had actually had happened to them,” she later recalled. “Everybody had suppressed all these feelings. …to this day there are many people that can’t talk about it.”

The testimony of Chiye and her fellow internees led to the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The law granted reparation payments to surviving internees and an official apology from the US government.

You can hear this all-star of Chicago Women’s History Month tell her own story in this video:

BADASS WOMEN OF CHICAGO HISTORY ON MARCH 22!

It’s an honor highlighting these ladies during Chicago Women’s History Month. They fought to make the city what it is today. So we hope to see you at “Badass Women of Chicago History” on March 22 to hear even more of their stories! Buy your tickets now to learn about a whole host of cool women. Our storytellers are introducing everyone from the mother of forensic science Frances Glessner Lee to the first African-American female pilot Bessie Coleman.

– Marie Rowley, Marketing Coordinator