Lincoln Yards, the controversial mega-development on the North Branch of the Chicago River, is just one of many enormous projects across the city. The sites, built by private developers with infusions of public money, aim to build entire neighborhoods from scratch. Obviously, these are “no little plans” as Daniel Burnham might say, and they have interesting antecedents dating back to the famous Burnham Plan. In order to understand the present building boom, let’s examine private mega-development history in Chicago.

We research stories from Chicago history, architecture and culture like this while developing our live virtual tours, in-person private tours, and custom content for corporate events. You can join us to experience Chicago’s stories in-person or online. We can also create custom tours and original content about this Chicago topic and countless others.

Make No Little Plans

The origins of the Chicago mega-development stretch back to the late 1800s. As Chicago rebuilt from the Great Fire young hotshot architects flocked to the city. Within just a few years, William LeBaron Jenney, Dankmar Adler, Louis Sullivan, John Wellborn Root, and, of course, Daniel Burnham set up shop in the boomtown of the prairie. These architects reimagined the possibilities of architectural form with the skyscraper, which only whetted their appetite. Burnham especially saw the opportunity to remake what an industrial American city could look and feel like.

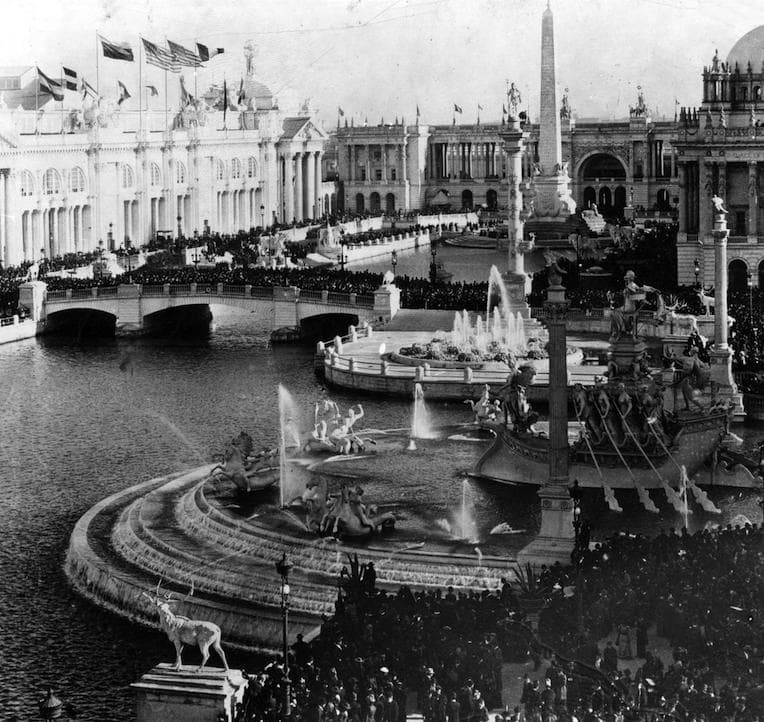

He oversaw the design and construction of the famous White City in 1893, which heralded Chicago’s arrival as a major world city. Burnham parlayed this success into a secondary career as a city planner. He exported his “City Beautiful” aesthetics into the new city plans for Manila, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Eventually, he turned his eye for grand Beaux Arts urban planning back on his hometown.

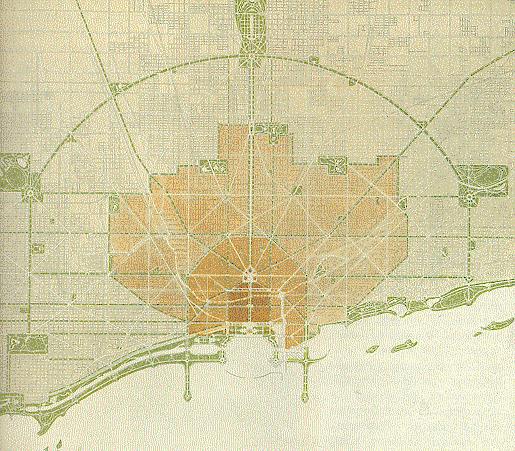

The famous Burnham Plan of Chicago reimagined the dusky, brawling industrial boomtown as a Paris on the prairies. Iconic elements of the cityscape like Grant Park, Museum Campus, Navy Pier, Wacker Drive and the Mag Mile are the legacy of Burnham’s plan. His sweeping vision, made famous by the (non!) apocryphal adage “make no little plans,” encouraged later developers to similarly monumental ambitions, perhaps seeding the idea for the instant neighborhoods of mega-developments like Lincoln Yards.

Bringing Residents Back to Downtown

The second Mayor Daley’s 21 years in office provides a more direct historical antecedent to today’s massive mega-developments. By the 1960s, suburbanization and the rise of TV culture meant that the Loop emptied out by 6pm. So the Daley Administration orchestrated residential redevelopments of old industrial spaces in and around the Loop.

The first neighborhood that City Hall redeveloped was the South Loop. Long a warren of factories, warehouses, and train depots, the South Loop offered a wealth of real estate which was suddenly available when the train lines went belly up. Station closures left hundreds of acres of empty train yards in the South Loop. The first mega-development to swoop in on this territory was Dearborn Park. The residential development stretches for a mile south of the rehabbed station, plopping an enormous amount of housing stock into an area which hadn’t seen it in over a century. We can visit the area on our private tours of downtown.

Similar residential or mixed-use redevelopments of old train yards soon sprang into action around downtown. Sale of air rights turned the old Illinois Central depot just east of Michigan Avenue into the Illinois Center and Lakeshore East. The Grand Central and Van Buren train yards had patchwork developments, most notably River City and the Roosevelt Collection. River North’s old harbor district, east of Michigan Avenue on the north bank, became Cityfront Center. The ground of Central Station, just west of Museum Campus and south of Grant Park, into a new neighborhood of highrises and lofts named Central Station. Mayor Daley even moved into a condo there in the early 90s. Our guests see almost all of these developments on our private tours of downtown or Chicago neighborhoods.

Rebuilding in the Heart of the Loop

Mega-projects are not just limited to old industrial districts, of course. Enchanted by Modernism’s glittering glass towers and seduced by the dreams of urban planners who rather hated urban spaces, City Hall decided that the historic heart of the Loop had to go. Historic structures like Louis Sullivan’s Stock Exchange and the enormous Sherman and Morrison Hotels met the wrecking ball in the ’60s and ’70s.

Apparently unsatisfied going one building at a time, the city sometimes demolished entire blocks of buildings in those years. Today’s Daley Center plaza used to be a dense collection of old buildings, including the beloved restaurant Henrici’s. City planners condemned and cleared them all to build Mayor Daley’s new Civic Center, which eventually bore his name. Across Dearborn Street, the city spent over a decade buying up every structure on Block 37, including the landmarked McCarthy Building. They all came down in 1989, leaving a gaping hole on the site for 20 years.

Bad as that sounds, it was nearly worse. City Hall created a North Loop Redevelopment District in 1973. In essence, they declared everything north of Washington and east of Clark to be a slum. Developers floated plans to demolish virtually everything and replace it with a set of interlocking towers, sky bridges, and pedways ala the Illinois Center. Thank goodness it never came to pass. Imagine no Marshall Field’s on State Street or no glittering Tiffany dome at the Chicago Cultural Center.

The Debate Over Mega-Development Today

Big as these past projects were, the current building boom may outpace them all. Virtually all real estate along the North and South Branches of the Chicago River is being converted. The biggest break with the past is how privatized this phase of construction is. Under the Daleys, the city usually took the lead in clearing old structures and guiding redevelopment. These days such work is done by private developers like Sterling Bay and Related Midwest. All they need is occasional green lights from City Hall to remake Chicago as they see fit.

Mega-projects like Lincoln Yards and The 78 almost always create opposition, but the privatization of the process changes that dynamic. Sterling Bay and Related Midwest are not responsible to the people of Chicago, but to their shareholders. Thus, they have less incentive to listen to the communities being disrupted or hew to the extant cityscape. Despite this, they’re getting hundreds of millions in taxpayer money to fund construction. So far, that’s meant these big plans are meeting unprecedentedly big opposition.

– Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide

ABOUT CHICAGO DETOURS

Chicago Detours is a boutique tour company passionate about connecting people to places and each other through the power of storytelling. We bring curious people to explore, learn and interact with Chicago’s history, architecture and culture through in-person private group tours, content production, and virtual tours.