This week marks the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Chicago race riot. One mostly-forgotten man’s camera captured the city’s violence and tension with a firsthand view. The remarkable life of photographer Jun Fujita, and his experience as a Japanese American working in the midst of the race riots, shed a new light on this volatile and terribly-relevant period in our history.

We research stories from Chicago history, architecture and culture like this while developing our live virtual tours, in-person private tours, and custom content for corporate events. You can join us to experience Chicago’s stories in-person or online. We can also create custom tours and original content about this Chicago topic and countless others.

How the 1919 Race Riot Happened

During the 1919 Chicago race riot, racial violence tore apart the city for seven long, bloody days. In the end, 38 people died and over 500 were wounded.

A young black boy named Eugene Williams swam past the invisible line demarcating the black and white beaches on the Lake Michigan shore. Angry white swimmers threw stones at him. Someone threw a stone that hit Eugene’s head, and he sank below the waves and drowned. The Chicago police refused to arrest the white perpetrators, instead arresting a black man who voiced his outrage. This injustice prompted a black crowd to assemble in protest at the 29th Street Beach. White mobs responded with violent reprisals.

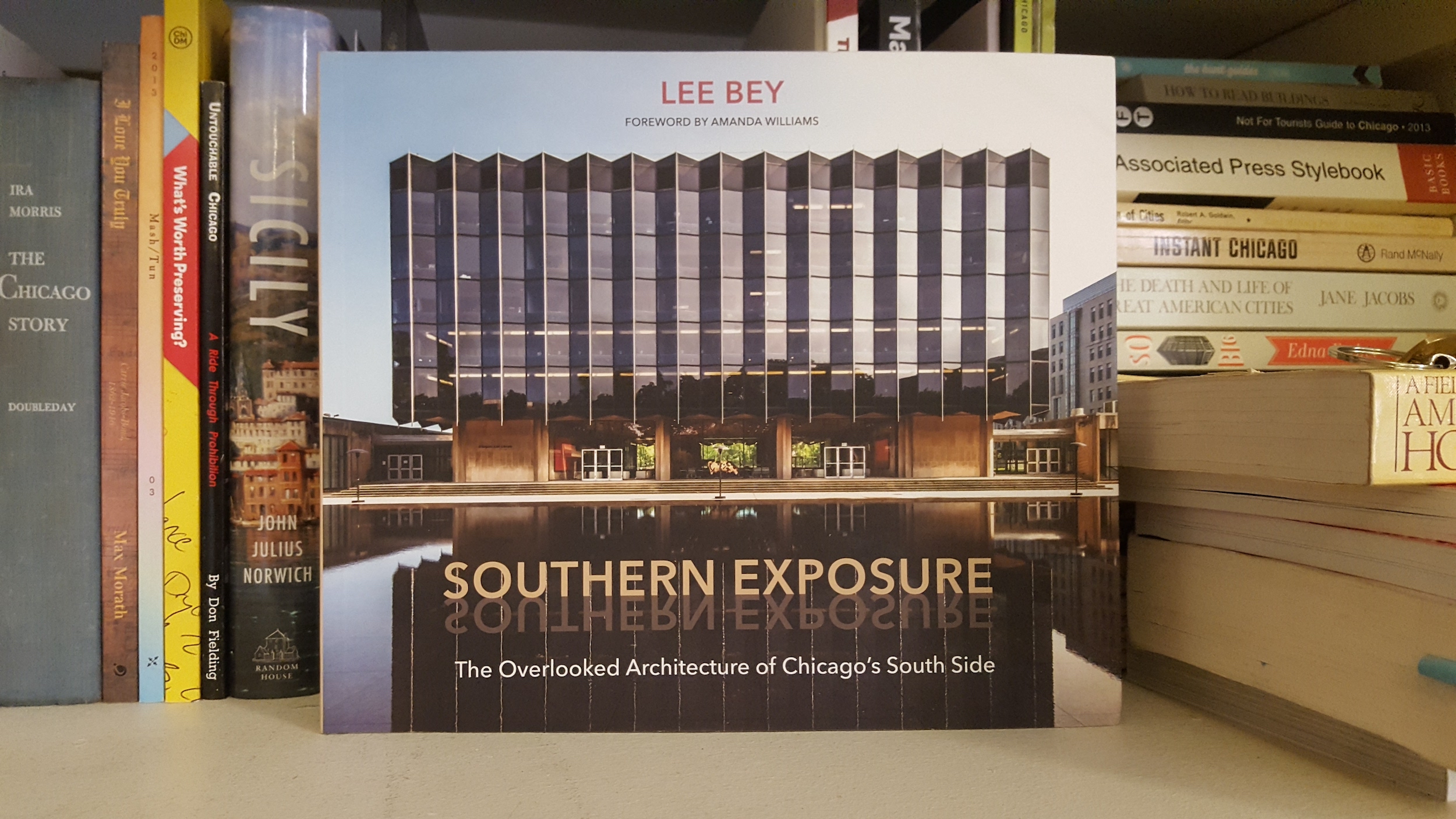

The 1919 Chicago race riot was the worst episode of racist violence in the notorious “Red Summer.” The social and physical scars it left in the city are still visible a century later. Many organizations, writers, and artists are spending this year commemorating the anniversary. I was especially impressed with Eve L. Ewing’s new book, which is titled 1919. Such work will hopefully teach more people about this awful injustice and help heal our divided city. Their work is vital, especially in the current political climate.

Jun Fujita

The images we have today of the 1919 race riot are almost all from the camera of Jun Fujita. Born near Hiroshima in 1888, he emigrated to Canada and then Chicago as a young man. He graduated from Wendell Phillips Academy and paid his Armour Institute tuition by working as a photojournalist for the Chicago Evening Post. His work for the Post (and later the Chicago Daily News) brought Fujita to the site of Chicago’s most violent and infamous incidents in the 1910s and ’20s. His photos of the Eastland sinking and the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre are the most widely-known images from those horrific events. Fujita’s striking monochrome photos of the Indiana Dunes and Tanka poetry belie a man whose soulfulness suffused both his work and life.

The thoughtful nature of his work owes a lot to the precarious and dangerous situation that Japanese-Americans faced a century ago. Fujita was a member of the Issei generation, who emigrated to the U.S. before the Immigration Act of 1924 banned further Japanese immigrants. American laws forbade them, like other immigrant communities from Asia, from citizenship and most legal rights. Larger groups, like the Chinese, created thriving – albeit highly segregated – neighborhoods for themselves.

Japanese Chicagoans, like Fujita, had no such social structure to fall back upon. He faced personal prejudice, social stigmatization, and legal discrimination by himself. Most tellingly, Fujita could not marry his partner, a white female journalist named Florence Carr, because of anti-miscegenation laws. He only became an honorary citizen via an act of Congress in the 1950s. Fujita died before Japanese-Americans were eligible for naturalization.

The Terrifying Impact of the 1919 Chicago Race Riot

No moment in Fujita’s long career as America’s first Japanese photojournalist was as consequential and personally dangerous as the race riots. The violence unleashed that week mostly came from white mobs, who attacked African-Americans in the Black Belt, on streetcars, at the Stock Yards, and even on the streets of the Loop.

The “athletic clubs” of Bridgeport, essentially gangs of young men tied to a particular politician’s club, were major instigators. They launched raids against black neighborhoods with the passive or active assistance of the police. Some even dressed up in blackface to torch Polish and Lithuanian-owned buildings in Back of the Yards and Canaryville to rile up racist resentment. They were the foot soldiers in a pogrom of racist violence. It’s not an exaggeration to say that this mob violence is the Northern equivalent to Jim Crow South’s lynchings. The white violence, along with the self-defense of the Black community, hardened racial lines and led directly to today’s segregated city.

More than a Black and White Incident

Notably, the violence did not just have black and white victims. Mexicans, still a small ethnic community at the time, were targeted and violently attacked as well. Bigotry and the pseudoscience of eugenics led authorities to ban immigration from countries like Poland and Italy. Racial animus against Asian-Americans was extremely strong at the time, as well. As noted before, Asian immigrants could not be naturalized and were the only racial group to face de jure segregation outside of the South. Anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese violence frequently swept through the West Coast.

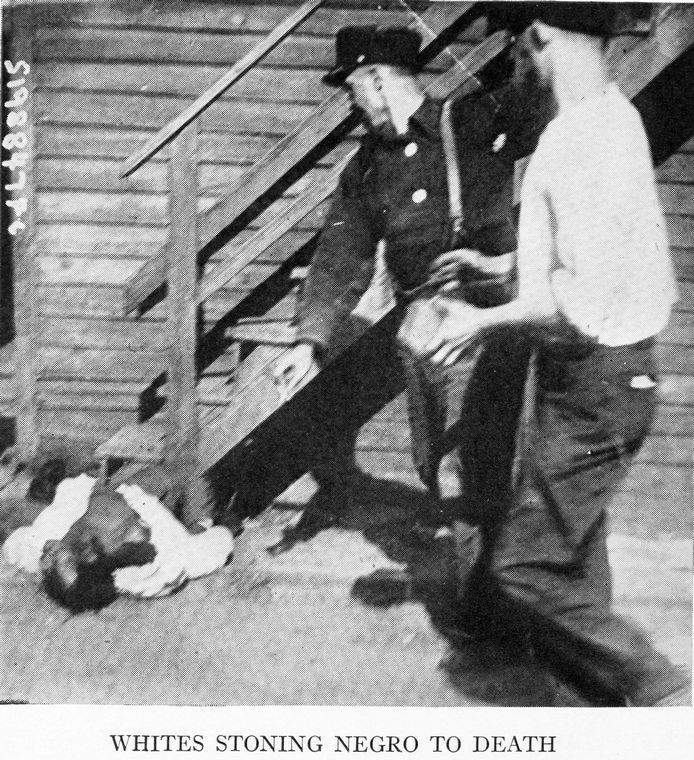

Considering all of that, Jun Fujita’s photographs of the 1919 riots demonstrate astounding personal bravery. The most searing set of photos he took during that week captured a black man’s death. He photographed a white mob as they chased a black man into a yard and then beat his brains out with bricks. Fujita, a member of an often-reviled minority group, stood literally feet away from this mob violence. The mob might very well have turned on him as its next victim.

Even more incredibly, Fujita’s photos are basically all the visual evidence we have of the riots. Photojournalism was still a very new field at the time. Many news outlets still relied on illustrations. So Fujita may have been the only person with a camera in that battle zone. If not for his bravery and skill these immediate, tactile, terrifying images would not exist. A century later, as we still struggle with the legacy of the riots, I think every Chicagoan owes Jun Fujita a great deal of gratitude.

-Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide

ABOUT CHICAGO DETOURS

Chicago Detours is a boutique tour company passionate about connecting people to places and each other through the power of storytelling. We bring curious people to explore, learn and interact with Chicago’s history, architecture and culture through in-person private group tours, content production, and virtual tours.