The Illinois Bicentennial is coming up on December 3rd. We became the 21st state to enter the Union on that date in 1818.

So take that, Alabama, you 23rd-place dogs! <shakes fist at some random Crimson Tide fans> Ahem. My apologies. Don’t know what came over me.

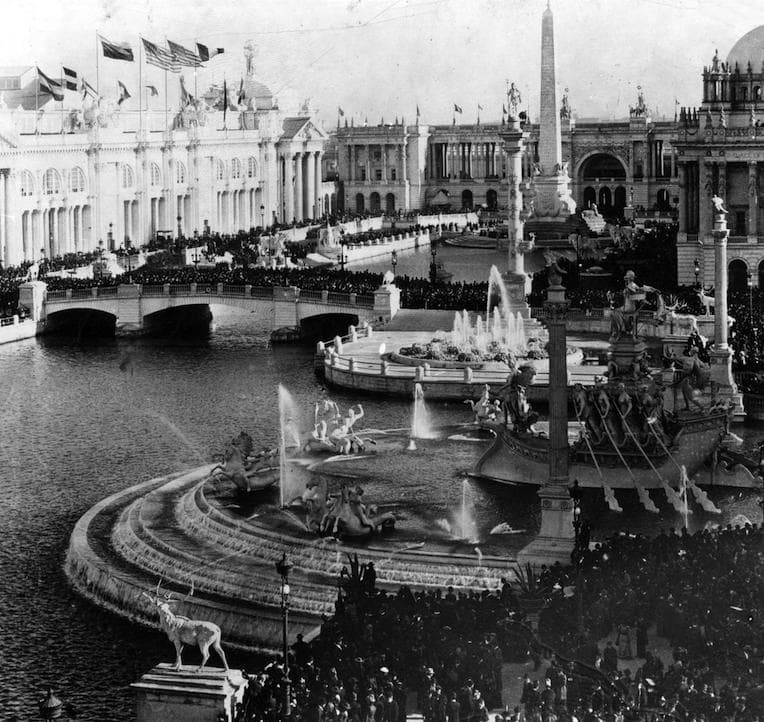

Illinois Bicentennial celebrations stretch across the state from Winthrop Harbor to Cairo, with Chicago hosting a massive party on Navy Pier on December 3rd. Considering the big date, we’re celebrating the Illinois Bicentennial by looking back to what Chicago was like 200 years ago.

We research stories from Chicago history, architecture and culture like this while developing our live virtual tours, in-person private tours, and custom content for corporate events. You can join us to experience Chicago’s stories in-person or online. We can also create custom tours and original content about this Chicago topic and countless others.

Chicago Was Almost Part of Wisconsin (!)

Congress carved the Illinois Territory, which included all of Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota and Michigan, out of the old Northwest Territory (hence Northwestern University) in 1809. The southern part of the Territory became the State of Illinois on December 3rd, 1818.

The new state’s northern border would’ve been in the Joliet region, south of Chicago. Illinois’ Congressional delegate Nathaniel Pope proposed bumping the border 60 miles north to give the new state access to Lake Michigan. If not for Pope’s proposal, I’d be writing from Chicago, Wisconsin and looking down my nose at the bumpkins celebrating their Illinois bicentennial. Perish the thought.

The DuSable/Kinzie Estate

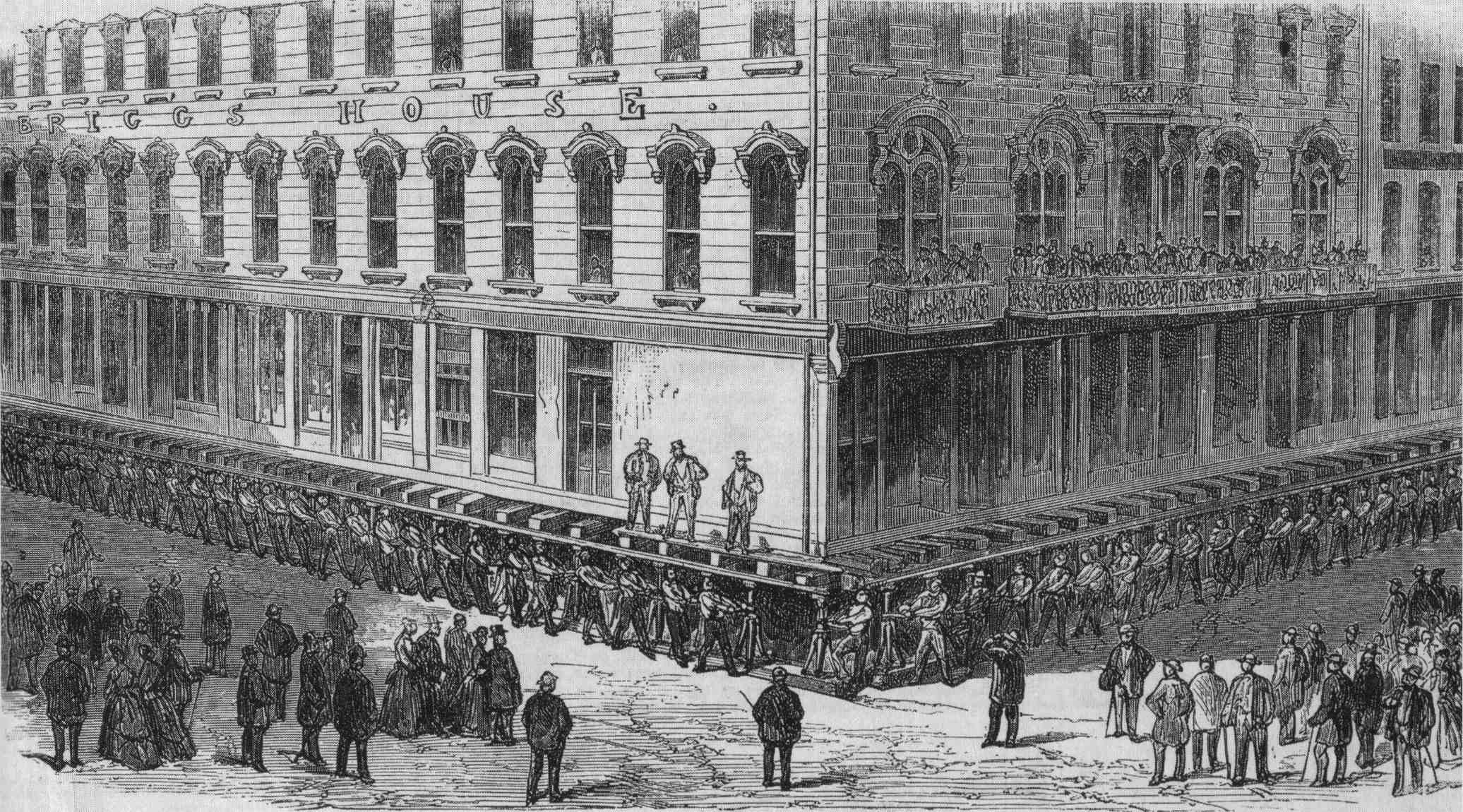

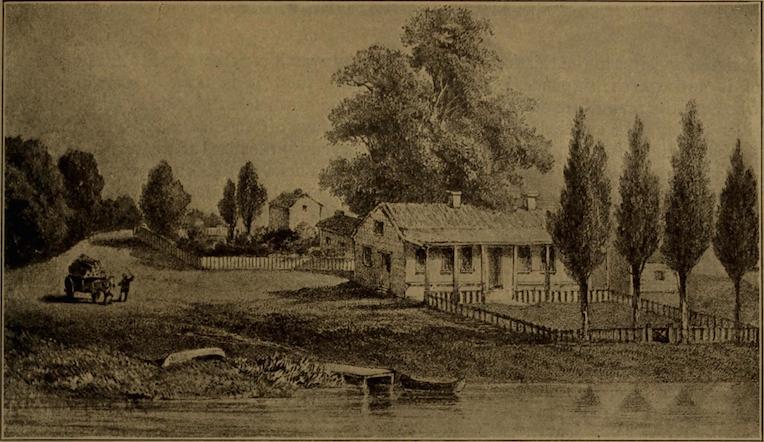

Visitors to Chicago in 1818 would almost certainly have paid a visit to the Kinzie house. The house and trading post were originally built around 1790 by Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, a mixed-race trader who is widely regarded as the founder of Chicago. According to the bill of sale from 1800, du Sable’s Chicago estate had a spacious log cabin with furniture and paintings, as well as “…two barns, a horse drawn mill, a bakehouse, a poultry house, a dairy, and a smokehouse.” Quite the deluxe spread! No, but seriously, that was an extremely impressive spread for this region at that time. It’s always a pleasure to point out the spot during our Downtown Bucket List tours.

A Canadian trader, John Kinzie, moved into the estate with his family in 1803. The trading post flourished under his stewardship, though he did flee the area in the 1810s after committing Chicago’s first murder. He also may have been a traitorous scoundrel who orchestrated the massacre of the Fort Dearborn massacre to cover up the murder he’d committed. Kinzie returned to Chicago after the war, pretended all was fine, and portrayed himself as the founder of Chicago because the actual founders and witnesses were dead. Holy shit!

Despite this ignominious exit, the Kinzie house served as a local landmark and informal inn during the tiny frontier town’s earliest decades. A traveler who stayed in the house in 1817 recounted the cozy layout of the building: “The front door opened into a wide hall, that hospitably led into the kitchen, which was spacious and bright, made so by the large fire-place.” What a welcome sight this little outpost must have been for weary travelers!

Fort Dearborn

The U.S. government built a Fort Dearborn directly across the river from du Sable’s estate in 1803 to protect the Chicago portage, an invaluable connection between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River waterways. It quickly became the bustling center of the frontier community, with over 100 soldiers stationed there.

The site where the fort once stood is now the intersection of Michigan and Wacker. You’ll have to wait until it’s warmer, but our custom private tours of downtown can delve into how dramatically this exact point has changed in 200 years. Back then, the wooden fort sat on a bluff overlooking a huge bend in the Chicago River. Today, the intersection is artificially elevated dozens of feet above the river below. Bronze plaques in the sidewalk trace its outline for passersby.

Ante Urbem in Horto

A visitor to Chicago in 1818 would have found precious little beyond the trading post and fort. Crazy as it may sound at the Illinois Bicentennial, but this huge and sprawling metropolis was merely a rural backwater in 1818. Illinois’ population and economic centers were concentrated in the central-south part of the state. The Chicago River area, despite the prominent portage, was still the back of beyond.

The defining feature of Chicago’s landscape back then was the vast flat expanse of the prairies. These endless undulating grasslands extended across the northern 2/3rds of the state. The so-called “sea of grass” astounded early European and American explorers and settlers. In fact, the landscape terrified many visitors because it lacked distinguishing landmarks for navigation. Pioneers could disappear into the ten foot tall grasses and never reappear. Some woods clustered near the riverbanks and covered stretches of the North Side, but the prairies dominated.

Wildly Different Waterways

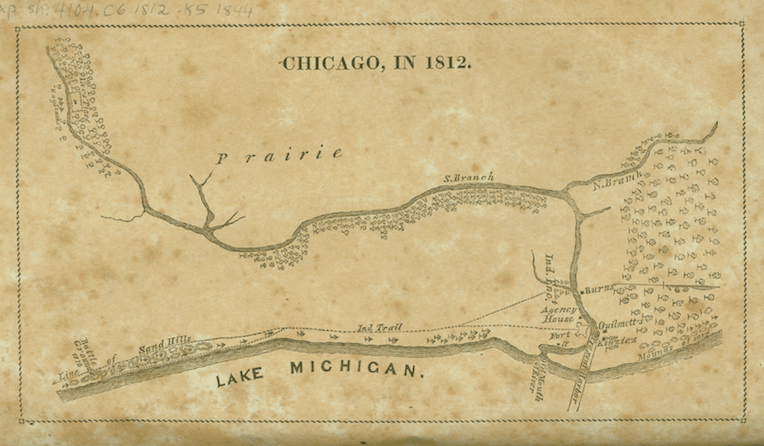

The waterways of 1818 would baffle current residents of Chicago. The river took a meandering course at the lakefront. As the image above shows, the river flowed south for another half-mile. It emptied into Lake Michigan near the present-day intersection of Michigan and Madison. A sandbar cut Fort Dearborn off from the lake. The Army Corps of Engineers finally dredged it in the 1830s, thereby creating Streeterville.

The lakefront itself was also in a very different spot back then. Anyone wandering Grant Park during the Illinois Bicentennial this year would have found themselves neck deep in water in the same spot back in 1818. In that day, the waters of Lake Michigan lapped onto sandy beaches on the line of today’s Michigan Avenue. All the land east of that is artificial landfill, built on debris from the Great Fire of 1871 and huge public works in the early 20th Century.

Last Days of the First Chicagoans

Of course, Native Americans had traveled those natural waterways for many generations. The Potawatomi had lived in the Chicago region for at least 200 years when Illinois became a state. A recent Curious City article shows the many Native villages which dotted the Chicago region, as well as a snake-shaped effigy mound in what’s now Lakeview. Another article from Curious City delves deeply into the welcoming and relatively-cosmopolitan nature of Potawatomi society.

Indeed, a majority of the inhabitants of Chicago in 1818 would’ve been Native American or Métis, people of mixed European and Native American ancestry. Indeed, Chicago residents elected a notable Métis resident named Billy Caldwell Justice of the Peace in 1825. Pressure from White settlers from the East and subsequent American military actions and treaties led to the removal of the Native Tribes by the 1830s. Some Métis inhabitants moved west with their Native relatives, while others assimilated into the new city.

Looking Back During the Illinois Bicentennial

An anniversary like the Illinois Bicentennial is a boon to history nerds like myself. For one, it lets me unleash waves upon waves of historical information. (You’re welcome.) More importantly, though, it encourages us to look back and put our own experiences into the broader sweep of history. It’s remarkable how much this nowhere prairie hamlet on the windswept shores of Lake Michigan has transformed. One cannot even imagine Illinois history without Chicago during the bicentennial, but no one alive in 1818 had any clue how significant the tiny town would become. Let that be a lesson to you.

– Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide

ABOUT CHICAGO DETOURS

Chicago Detours is a boutique tour company passionate about connecting people to places and each other through the power of storytelling. We bring curious people to explore, learn and interact with Chicago’s history, architecture and culture through in-person private group tours, content production, and virtual tours.