How has the city of Chicago responded to previous epidemics in our history? The current Coronavirus pandemic has shuttered Chicago unlike any other event in living memory. History is happening now. As of today, all schools, restaurants, bars, and public gatherings have been shut down. These containment efforts are the latest chapter in a story that goes back to the very founding of Chicago. Urban environments, especially a vast metropolis like ours, have been hot spots for contagion throughout human history.

To help put the current efforts to “flatten the curve” into context, we ought to look back at previous tactics Chicago used to battle pandemics. Some rather distinctive physical features of Chicago’s cityscape are actually direct responses to disease and contagion.

We research stories from Chicago history, architecture and culture like this while developing our live virtual tours, in-person private tours, and custom content for corporate events. You can join us to experience Chicago’s stories in-person or online. We can also create custom tours and original content about this Chicago topic and countless others.

Raising the City

Public health crises have threatened Chicago across its history. Cholera ravaged the population as early as the founding of the village of Chicago in 1832. Though medical science wouldn’t be able to comprehend and treat the issue for decades, it was Chicago’s watery setting which exacted a dreadful toll on its citizens. Our city is built atop a marshland, with a small prairie river draining directly into Lake Michigan. A setting that is, in all honesty, the dead opposite of ideal for avoiding waterborne contagions like cholera. The city’s streets and waterways were notoriously noxious–filled with human, animal, and industrial waste.

The city made repeated efforts to rid itself of potential contagions. Some initial efforts, like street sweeping, were comically misguided. Yet others, along with medical advancements, have made Chicago a more sanitary city.

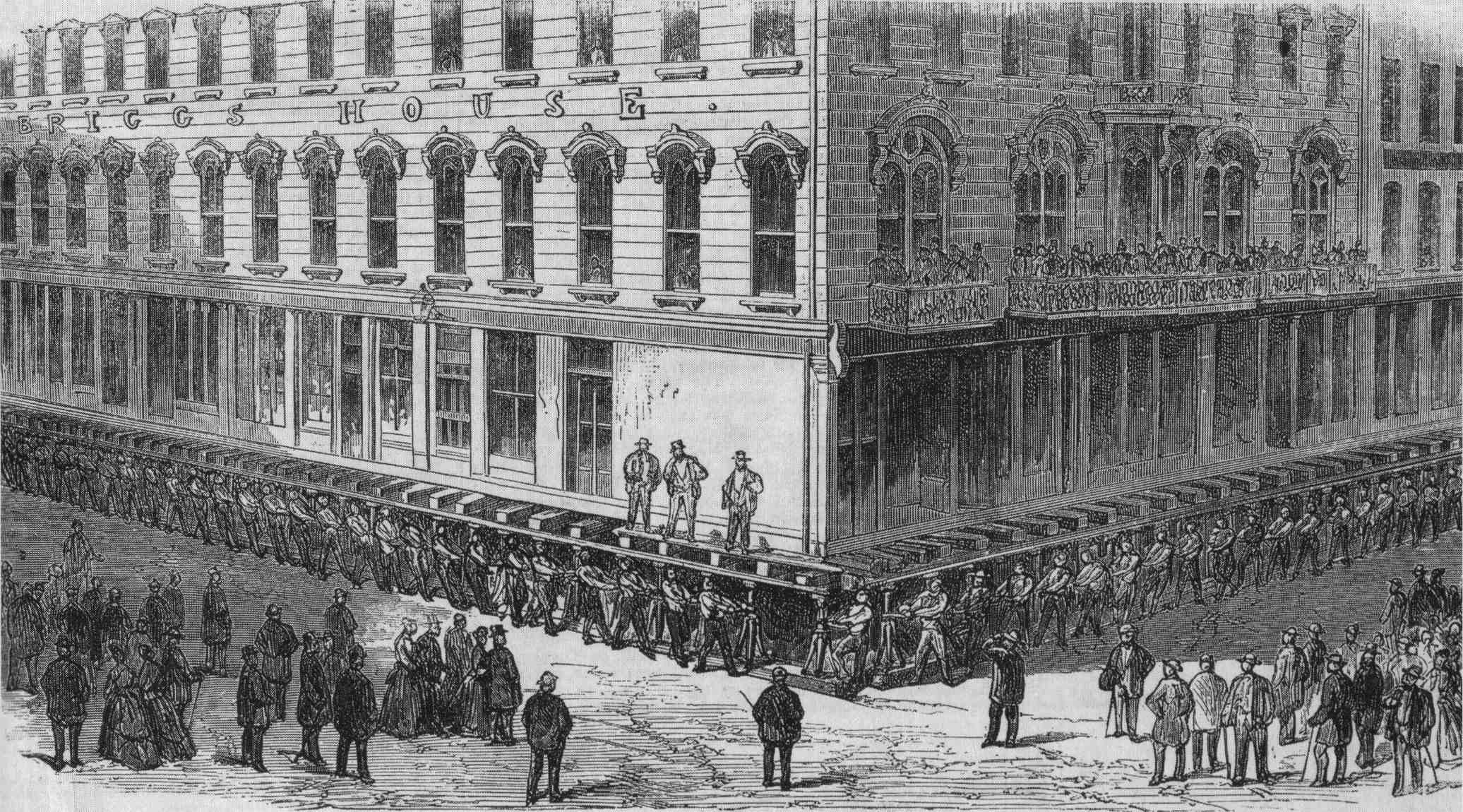

The city hired famed sewer engineer Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough to solve its wastewater problem. Yes, I swear, this dude really was famous for his sewage engineering! Chesbrough knew that digging into the waterlogged layers of hardpan and clay would be a ton of work and a giant mess. (These layers would also confound architectural engineers). So in the 1850s, he advised that the city rise up instead.

Subsequently, workers laid sewers at the existing street level. They then piled a new surface atop. Part of this process was also to elaborately jack buildings up to the new street level, sometimes as high as ten feet. This process was repeated in even-grander fashion with the famous Upper and Lower streets. These route trash, deliveries, and other potentially obstructive or unhealthy services away from the public. So, when you see our layer cake of a city rising up from the Chicago River, you can thank Chesbrough and Burnham.

Reversing the Flow of the Chicago River

Many boat tour guides may say that Chicago’s most dramatic effort to fight disease was the reversal of the Chicago River. Even with the streets raised, the river indeed remained a stinking sewer. Nauseatingly, the Union Stock Yards dumped its toxic waste into “Bubbly Creek,” which poured directly into the South Branch. Such dangerous waste flowed down the river and into Lake Michigan, the source of Chicago’s drinking water. According to legend, an 1885 storm flushed so much sewage into the lake that it caused an outbreak of cholera which killed 90,000 people. Happily, that story is just a legend. Rumor has it that the story was concocted to launch the TARP project in the 1970s. Regardless, sending wastewater into Lake Michigan was asking for an epidemic for much of Chicago’s early history.

When it was completed in 1900, the Sanitary and Ship Canal saved lives by reversing nature itself. The US Army Corps of Engineers built a damn and canal across the mouth of the river in downtown. They also cut a canal from the North Branch to Wilmette. Another canal connected the South Branch with the Des Plains River and the Calumet River. This vast engineering job sent all of Chicago’s water upstream, towards downstate Illinois and the Mississippi River basin. (The latter was much to the chagrin of St. Louis).

The removal of contagions from Chicago’s water supply removed much of the danger of epidemic that had felled so many. When we do private boat tours, we like to remind people of what an incredible feat this was – not just for the time, but for all of history.

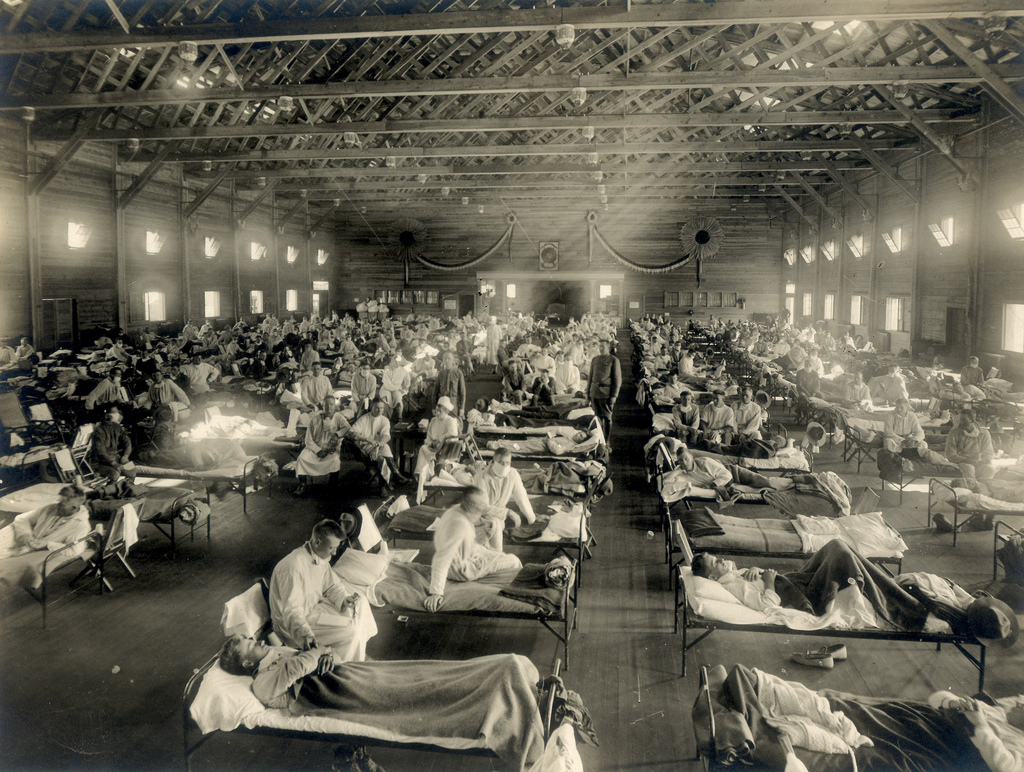

The 1918 Flu Pandemic in Chicago

The 1918 flu outbreak was among the worst disaster in Chicago’s history. The local response to the 1918 flu has direct parallels and lessons for the current Coronavirus pandemic. We delved into what happened in this piece.

Chicago Detours in the Time of Coronavirus

We tell this history because history is happening right now. The safety of our tour guests and staff is top priority on our tours. We have been employing the hygiene and social distancing precautions outlined by the CDC and the Chicago Department of Public Health. As the city has shuttered, so have we. We have cancelled tours until March 31, at least. This tour cancellation period may extend further.

Wishing you and yours health and safety.

– Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide

ABOUT CHICAGO DETOURS

Chicago Detours is a boutique tour company passionate about connecting people to places and each other through the power of storytelling. We bring curious people to explore, learn and interact with Chicago’s history, architecture and culture through in-person private group tours, content production, and virtual tours.