As a tour guide with Chicago Detours, I promised a number of “curious people” on our Loop Interior Architecture Walking Tour that I would try to hunt down answers to their questions.

How was the Chicago Picasso built? I consulted the Chicago Public Library’s historical chronology of the piece, as well as a Chicago Tribune special “Chicago Days” article. Working from France, Picasso made a 42” maquette, or model, of the work. The American Bridge Division of U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana then fabricated the final 50-foot tall piece using this model. Working under the supervision of Chicago Civic Center architects and engineers, workers preassembled the sculpture in Gary, then disassembled it and shipped it to the Civic Center, where it was reassembled. Because it’s made of Cor-Ten steel, the same material used in the Civic Center, it’s acquired the same patina over time.

Picasso’s maquette, made of simulated and oxidized welded steel, is on display at the Rubloff Lobby at the Art Institute of Chicago.

How were the mosaics in the Cultural Center’s breathtaking Preston Bradley Hall made? I wrote to Rolph Achilles, an art historian who teaches at SAIC and curates the Smith Museum of Stained Glass at Navy Pier.

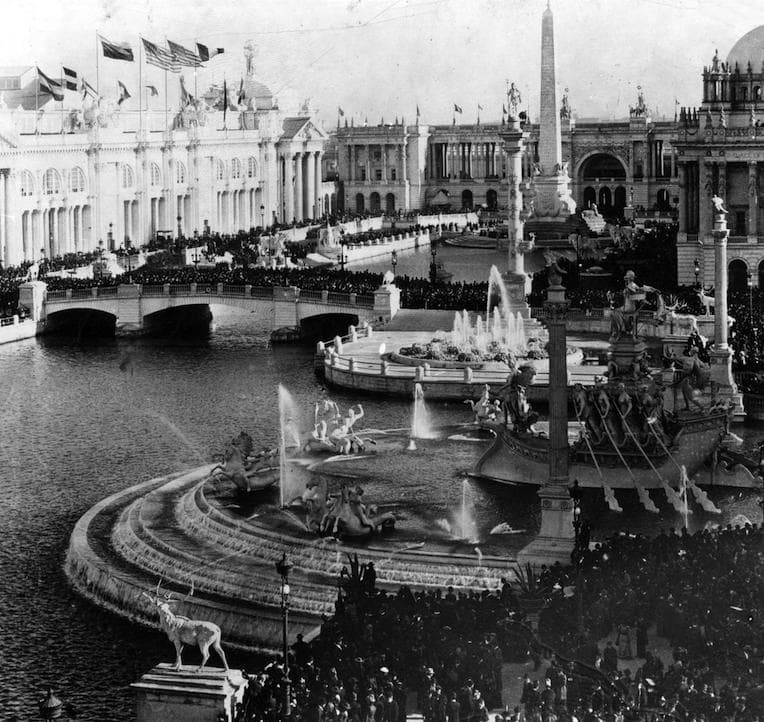

According to Rolph, those mosaics were probably designed by Jacob Adolphus Holzer, a Swiss artist who arrived in Chicago to design Louis Comfort Tiffany’s chapel at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. As Tiffany’s top mosaic guy, Holzer did several known installations of his own design, always using Tiffany product.

Here’s what Rolph had to say about the process by which the individual tiles in the mosaics, called tessera, were applied: “Mosaics for the Cultural Center were probably made in Chicago. The individual tessera were cut and glued on a cloth webbing, a mesh, in the pattern you see, in a shop. The tessera were applied one at a time to the mesh, NOT applied one at a time to the wall. The sheets were about 3×3 feet. The sheets were then applied to the wall with the pattern facing the room, filled in as needed along the edges and grouted. The mosaic insets in the marble are set in troughs cut into the marble. Then grouted.

“This technique is known by its medieval Italian name, cosmati. The CC is the finest example of the revival of medieval cosmati work in the US. The mosaics are a combination of glass and marble. There were highly skilled craftspeople in Chicago in the 1890s who could have assisted in this major project.”

“This technique is known by its medieval Italian name, cosmati. The CC is the finest example of the revival of medieval cosmati work in the US. The mosaics are a combination of glass and marble. There were highly skilled craftspeople in Chicago in the 1890s who could have assisted in this major project.”

And, according to the Cultural Center, much of the glass tessera in the mosaics was Tiffany’s patented favrile glass, made from mixing different colored glass together while still molten to achieve an iridescent quality.

What’s the name of the 1906 office building at 79 W. Monroe? It’s now called the Bell Savings and Loan Association Building—Bell Savings Building for short. According to city planner Ira J. Bach’s Chicago on Foot, it was formerly known as the Chicago Title and Trust Building. Original design was by the architect Jarvis Hunt, with a 1924 southern addition by Holabird and Roche. (Same firm that did the Chicago Temple.) And before that, it’s original name was the “Rector Building.” The modifications that we discuss on the tour were made in the late 1940s.

-Jennifer Slosar, Tour Guide