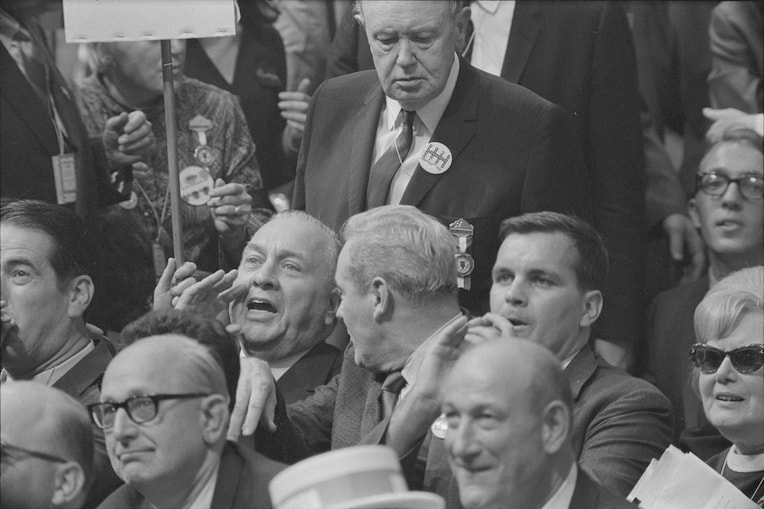

The 1968 DNC (Democratic National Convention) is among the most infamous and miserable events in Chicago’s history. Cops beating protestors. “The whole world is watching!” Mayor Daley sweating bullets and cussing out politicians. The DNC felt, still feels, like the culmination of an era. Post-war America ended in a sweaty convention hall and the contentious political and social world we know today was born on the streets of Chicago.

Fifty years later, I went to find some of the sites from the 1968 DNC. What I found, instead, was that this iconic moment has been expunged from present-day Chicago. Precious little trace of these events exists in anything but media or memory. Which leads me to ask, where’s the historic marker for the 1968 Democratic National Convention?

We research stories from Chicago history, architecture and culture like this while developing our live virtual tours, in-person private tours, and custom content for corporate events. You can join us to experience Chicago’s stories in-person or online. We can also create custom tours and original content about this Chicago topic and countless others.

What Made the 1968 DNC So Contentious?

Um, almost everything going on in American society and politics.

At least, that’s how it feels with hindsight. The Democratic Party had been in power for most of the past 40 years. FDR, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson had guided the New Deal coalition through the Great Depression, WWII, the Korean War, the Red Scare, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Space Race. They’d created the modern American state and then rammed it into an un-winnable quagmire in Vietnam. The Democrats were the status quo, with all the good and bad which that entailed.

President Lyndon Johnson expanded the Vietnam War until it broke him politically. His announcement that he would not seek or accept renomination in 1968 unexpectedly opened up the field. Subsequent months only added more chaos. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in April, leading to dozens of riots, including in Chicago. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was the front-runner until his assassination in June 1968. That left Veep Hubert Humphrey and upstart Senator George McGovern, with party bosses like Mayor Daley favoring the former. The ultimate nominee and platform would be decided on the convention floor in Chicago.

Mayor Daley’s particular version of Chicago added tinder to the already-combustible atmosphere. City Hall had never exactly cultivated a open-minded atmosphere. The mayor’s well-noted antipathy towards the Civil Rights Movement and kneejerk support for the war curdled the civic apparatus even further. When Democrats, protestors, and journalists arrived in a city run by a capital-b Boss who would brook no transgressions. I highly recommend Mike Royko’s seminal Boss if you’d like to learn more about Daley’s Chicago.

“The Battle of Michigan Avenue”

The violent clash on Michigan Ave is the defining moment from the 1968 DNC. Democratic leaders and delegates holed up in the Conrad Hilton, which we’ve often led Downtown Bucket List tour guests past. The Chicago Police and Illinois National Guard deployed all around the hotel. A teeming throng of 10,000 anti-war protestors chanted and rallied in Grant Park. This was not the biggest protest during the convention, but the central location and subsequent drama made it immortal.

The inexorable clash between the authorities and the protestors on Chicago’s front lawn defined the city for decades. CBS’s Fred Turner reported on the violence of August 28, 1968. It’s one of the most unforgettable live accounts in American journalism.

“Now they’re moving in, the cops are moving and they are really belting these characters. They’re grabbing them, sticks are flailing. People are laying on the ground. I can see them, colored people. Cops are just belting them; cops are just laying it in. There’s piles of bodies on the street. There’s no question about it. You can hear the screams, and there’s a guy they’re just dragging along the street and they don’t care. I don’t think … I don’t know if he’s alive or dead. Holy Jesus, look at him. Five of them are belting him, really, oh, this man will never get up.”

Today, it’s hard to fathom that anything amiss ever happened at Michigan and Balbo. The whole world was, indeed, watching that police riot on Michigan Avenue. The spotlight has shifted far away since then. One can find no plaques or memorials to the violence and upheaval. Indeed, the site is as bucolic as any in the city. It’s a world away from 1968.

Other Sites from the 1968 DNC

The same disappearing act is true for the other major 1968 DNC sites. Some of that is understandable. The International Amphitheater, where the convention itself was held, was demolished in 1999. A modern industrial park sits on the site today. Something tells me that Aramark Uniform Services isn’t interested in having controversial monuments in their parking lot.

Old Town, the nexus of Chicago’s hippie scene in 1968, has been a bastion of upscale liberal gentrification for decades. Nearby Lincoln Park was the focal points of the Yippie protests during the 1968 DNC. In fact, the most indiscriminate and indefensible police violence happened in Lincoln Park. If there was any spot in town which might mark the events of August 1968 I’d expect it to be here. And yet…nothing.

The Value of Remembering the Bad Times

The conspicuous absence of any marker raises an interesting question: are we better off forgetting about what happened in 1968? The trauma from that year still echoes in our national consciousness today. One could make a solid case that it’s in our best interest, emotionally and socially, to leave such chaos safely in the past.

I am not someone who would make such a case, though. As difficult and painful as an incident like the 1968 DNC might be, we owe it to ourselves to remember it. Indeed, I think that stories and images which disturb our mythos or upend the common consensus of beliefs like the “narrative of progress” deserve a greater measure of commemoration. Moments like the DNC throw our long-held beliefs and assumptions about our city’s history into sharper contrast. Maybe I’m just a noodly academic who loves uncertainty too much, but I think a historical marker is the minimum for such incidents and moments.

Works of public art, like monuments and memorials, are a functional part of understanding who we are and where we come from. Locally, our statues, memorials, and works of public art tell the story of Chicago. They honor our greatest heroes, along with some disreputable fascists and racists. These streets have markers commemorating political violence and private moments of global significance. So that fact that the 1968 DNC is missing says an awful lot. To me, born a generation later, the lack of any commemoration says that Chicago, and the country at large, has yet to deal conclusively with the fallout from 1968.

– Alex Bean, Content Manager and Tour Guide

ABOUT CHICAGO DETOURS

Chicago Detours is a boutique tour company passionate about connecting people to places and each other through the power of storytelling. We bring curious people to explore, learn and interact with Chicago’s history, architecture and culture through in-person private group tours, content production, and virtual tours.