A sad truth about buildings is that they often come down. A great architect can build a great building and a savvy developer can buy it, demolish it and build a new one. In Chicago, with all our wonderful architecture, this is a song well sung.

Thinking on this idea of preservation, I decided to tour Chicago to find some buildings that were saved from the wrecking ball.

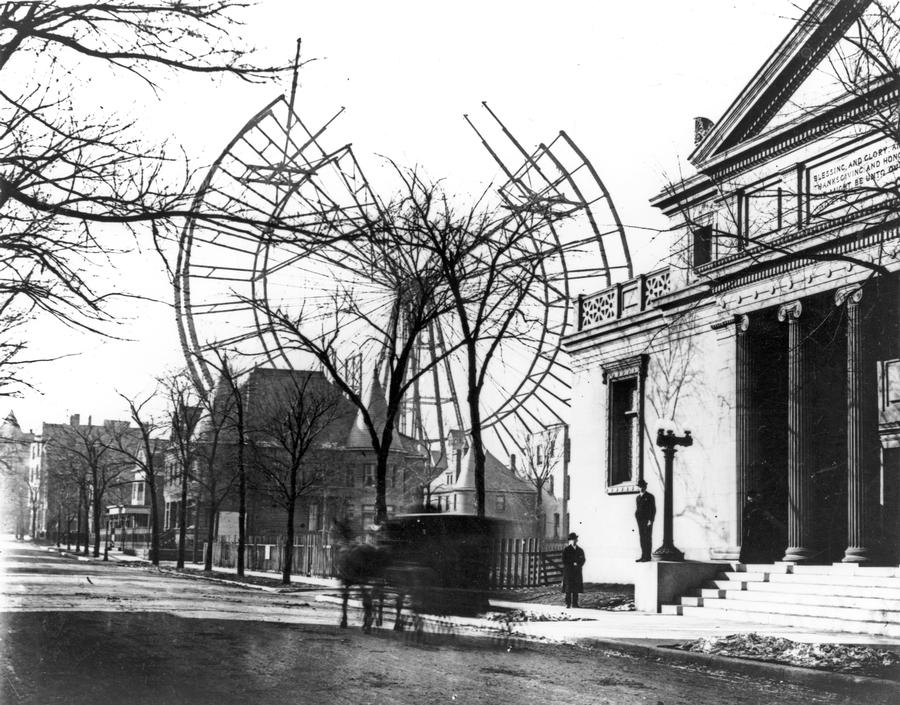

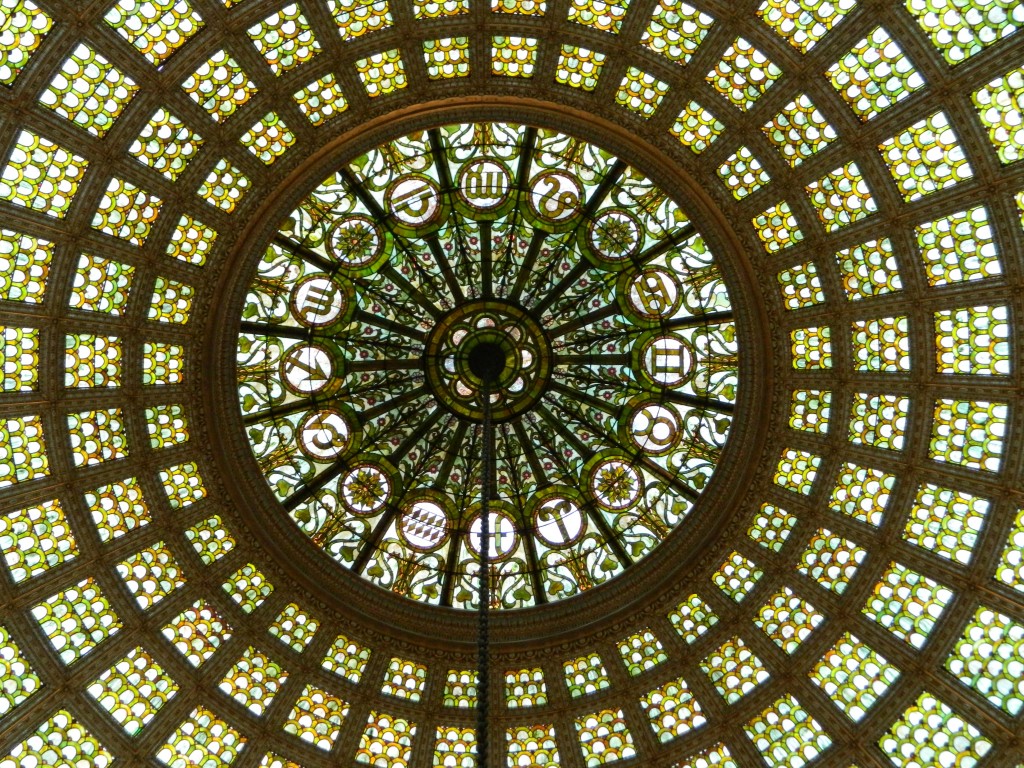

On my quest I began with a famous landmark of Chicago, the Chicago Cultural Center. Walking through this architectural masterpiece is a stunning experience. I went in through the south entrance, wandered up the winding staircase and gazed at the Tiffany stained-glass dome that we marvel at on our Loop Interior Architectural Tour.

The staircase is a wonder as well. Thousands of mosaic pieces decorate the marble and wind up and up, driving my curiosity as I ascended to the top floor. Really, how could anyone even think of demolishing this?

Depressingly easy answer for why buildings like the Cultural Center get torn down: money. Buildings cost money to construct and money to keep up. Though it may seem obvious to the average observer that buildings like the Cultural Center need to be preserved as historical landmarks, to the owner or developer of the property preservation isn’t so much a necessity. In fact, it’s probably very painful for the owners to watch their money evaporate in the rusty pipes and seep out through single-paned glass windows.

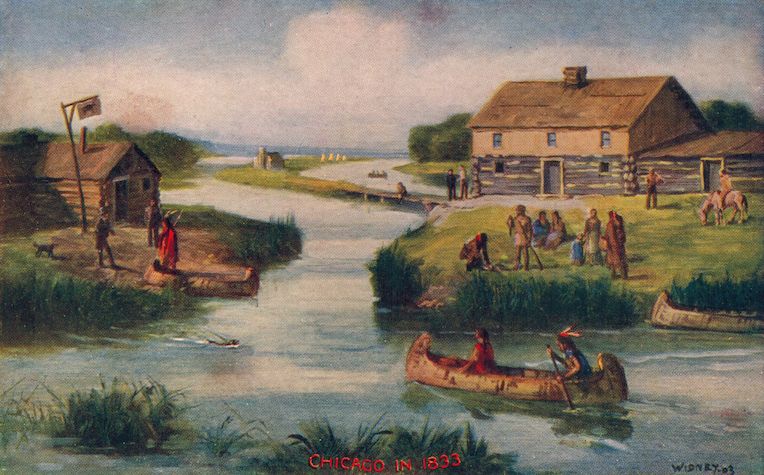

My other pick for luckiest building of the century is Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building. We visit it every week during the 1893 World’s Fair Tour.

Opened in 1889, the opening of the Auditorium Building brought senators, governors, even President Benjamin Harrison to its theater. One-hundred-and-fifty craftsmen guilded the interior with 50 million separate pieces of marble, 50,ooo square feet of mosaics, and 350 miles of electric wire and cable. This work of architecture is an engineering masterpiece. It was functionally outdated by the 1930s and demolition was discussed, but at that point in time the demolition cost was greater than the value of the land. It survived.

Thirty years later the discussion of demolition surfaced again, after Roosevelt University had purchased the building. This time the savior was Beatrice Spachner, “a violist with an iron will.” She set out with a $3.5 million fundraising campaign to restore the theater to its former opulence, and architect Harry Weese offered his services at no charge. It was a grand success.

I toured the exterior of this important Chicago landmark, and tried to take in the 17 million bricks that make up that block-long facade. To experience the 4,200 seat auditorium you can go to a show (there’s a ballet this weekend) or join the Auditorium Building’s architectural and historical tours.

These are just two of many Chicago buildings that have beat the wrecking ball. They survived from financial assistance, public outcry and political influence on their behalf.

However, many buildings of architectural significance have been erased from existence. I was shocked to hear just today that preservationists have withdrawn their lawsuit to save Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Hospital, built in 1975. To some the almost 40-year old building seems outdated, but imagine it was also around 40 years after construction of the Auditorium Building that demolition was first discussed. In the future Goldberg’s Prentice Hospital may have become more widely accepted for its unique cellular forms and advanced structural engineering.

If you would like to help preserve Chicago’s Landmarks or simply learn more about them, here are some good resources. Landmarks Illinois gives background on important historic architectural landmarks of Illinois, including those that are “endangered.” The City of Chicago Historic Preservation Department shares up-to-date information preservation efforts, and Preservation Chicago is a citizen’s organization focused on saving Chicago’s architectural and cultural history.

– Jenna Staff, Chicago Detours Editorial Intern